A few more bridge-related links recently seen:

Monstrous, Angelic, Unusual Bridge Sculptures

I like the Yokohama bridge turtle the best.

'Widespread opposition' to Barnard Castle suspension bridge plan

265m long suspension bridge would be the largest spanning footbridge in the country, but local residents can see better uses for £1.3m.

Joy as work finally set to start to restore Great Yarmouth’s Vauxhall Bridge

Historic span receives £630k makeover.

AZC: Bridge in Paris

This bridge was made for wobbling. Erm, I mean bouncing. Don't worry about the practicality, this is an entertaining bit of fluff.

Los Angeles Selects Ambitious Concrete Walkway for $401-Million Sixth Street Bridge Redesign

HNTB wins the competition with an expensive but spectacular design, pictured below.

22 October 2012

19 October 2012

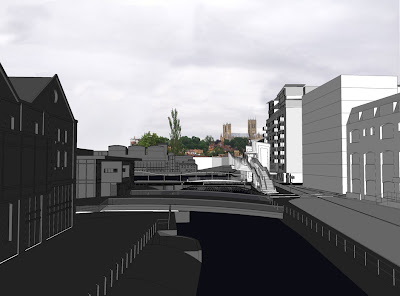

Brayford Level Crossing Footbridge, Lincoln

Network Rail has released images of a proposed new footbridge at Brayford Wharf East level crossing in Lincoln. This is the first of two architect-designed level-crossing footbridge schemes in the town intended to combat persistent mis-use of the level crossings. Images have been provided for public consultation in advance of a planning consent submission to be made in December.

The Brayford Wharf scheme is by Stem Architects, and by the standards of what Network Rail normally throw up for pedestrians, is architecturally somewhat extravagant. While I'm all in favour of context-sensitive design rather than simply dropping in identikit bridges, it seems at odds with the organisation's initiatives elsewhere to develop a more adaptable range of standard footbridge types.

Based purely on the images, my first reaction is it's over-wrought, a mass of texture that seems unnecessarily weighty. Although some transparent panels have been inserted into the elevation, there seems little interest in opening up the bridge user's views outwards, which strikes me as a key challenge given Network Rail's normal over-prescriptive approach to bridge design.

The Brayford Wharf scheme is by Stem Architects, and by the standards of what Network Rail normally throw up for pedestrians, is architecturally somewhat extravagant. While I'm all in favour of context-sensitive design rather than simply dropping in identikit bridges, it seems at odds with the organisation's initiatives elsewhere to develop a more adaptable range of standard footbridge types.

Based purely on the images, my first reaction is it's over-wrought, a mass of texture that seems unnecessarily weighty. Although some transparent panels have been inserted into the elevation, there seems little interest in opening up the bridge user's views outwards, which strikes me as a key challenge given Network Rail's normal over-prescriptive approach to bridge design.

16 October 2012

"Chinese Bridges" by Knapp & Ong

I've recently been reading "Chinese Bridges: Living Architecture from China's Past" by Ronald Knapp and Chester Ong (272pp, Tuttle Publishing, 2008) [amazon.co.uk] . Well, I say, reading, but for the most part I have been marvelling at the pictures.

. Well, I say, reading, but for the most part I have been marvelling at the pictures.

I'm not sure which Chinese bridges are best known worldwide, but I'd guess the most famous might include the Zhaozhou Bridge (pictured, below left, courtesy jrs65), Beijing's Jade Belt Bridge (pictured, below right, from the book), or the 2km Anping Bridge. All three are remarkable historic stone bridges, with the Zhaozhou Bridge particularly impressive for prefiguring similar Western achievements by many centuries.

More assiduous pontists will know that China is also in the midst of a truly massive bridge-building programme today: already, 8 of the 10 highest bridges in the world have been built in China, as well as 4 of the 10 longest spans.

However, the scale of the country is such that these represent only the tip of a very, very large iceberg. Luckily for us ignorant gwailo, Knapp and Ong's book helps expose a little more of China's vast and rich bridge heritage.

However, the scale of the country is such that these represent only the tip of a very, very large iceberg. Luckily for us ignorant gwailo, Knapp and Ong's book helps expose a little more of China's vast and rich bridge heritage.

It's a lovely coffee-table tome, amply illustrated with Ong's excellent photographs of bridges both famous and unknown. I don't think there's a page without a good photo on it. It also draws extensively on historic Chinese prints and paintings, and is clearly a labour of love.

The book is in three parts. The first is a general history of "ancient" Chinese bridge building, a journey through different bridge forms ranging across "step-on block bridges" (stepping stones), megalithic stone beam bridges, traditional chain bridges and more. One thing that is peculiar is that despite a wealth of detail, little is said on the bridge designers and builders themselves - there's no figure like Perronet or Telford here. Partly this is because the book's focus is before the "engineering" age of bridge building, but it may also relate to a lack of available information, or to the inability of individual bridge builders to build a reputation across such a huge country. This section introduces a number of bridges covered in more detail later in the book.

The second part addresses Chinese bridges as "living architecture", and discusses the relationship of traditional folk culture, feng shui, and religion to Chinese bridge building and use. Many historic Chinese bridges were or remain the sites of Buddhist, Taoist, or other temples, and many more are decorated with traditional emblems intended to bring good fortune or ward off disaster. Attention to auspicious dates and rituals played an important part in the building of many bridges, to the extent that bridges sometimes lay half-complete for considerable periods awaiting the "correct" date to proceed to the next stage.

The main part of the book is a gazetteer of over thirty particularly remarkable structures, "China's fine heritage bridges". Knapp's text for each bridge often ranges far and wide beyond the structure itself. When discussing the garden bridges of Beijing, for example, the reader will learn as much about the history of the Palace gardens as about the structures that ornament them. For others, like the canal bridges of Zhejiang, the text discusses in detail local trades and crafts.

Not all the bridges are spectacular - several are essentially minor structures of little fame or historical significance. However, they amply demonstrate the charm of vernacular bridge building, and that's reason enough to feature them.

Easily the highlight of the bridges included is a thirty-page section on Chinese covered wooden bridges, particularly of the "woven timber arch-beam" type. These are perhaps less well-known (Troyano's supposedly comprehensive Bridge Engineering: A Global Perspective ignores them, for example), but for me they are the main attraction of the entire book. While there are many examples of covered bridges throughout the book, this section concentrates on a particular sub-species, exemplified by rough-hewn behemoths like the Yangmeizhou Bridge (pictured, left, from the book).

While some in this group consist of straight beam bridges, with some similarities to the well-known covered bridges of Switzerland and the USA, most are massive timber "arches", supported by logs interlocked together in a polygonal form. The structure is generally hidden behind timber slat cladding, giving them a coarse, inelegant appearance. I find them quite beautiful.

Knapp's own website has a series of PDFs illustrating a variety of Chinese covered bridges, but it's no substitute for holding this exceptional book in your hands.

I'm not sure which Chinese bridges are best known worldwide, but I'd guess the most famous might include the Zhaozhou Bridge (pictured, below left, courtesy jrs65), Beijing's Jade Belt Bridge (pictured, below right, from the book), or the 2km Anping Bridge. All three are remarkable historic stone bridges, with the Zhaozhou Bridge particularly impressive for prefiguring similar Western achievements by many centuries.

More assiduous pontists will know that China is also in the midst of a truly massive bridge-building programme today: already, 8 of the 10 highest bridges in the world have been built in China, as well as 4 of the 10 longest spans.

However, the scale of the country is such that these represent only the tip of a very, very large iceberg. Luckily for us ignorant gwailo, Knapp and Ong's book helps expose a little more of China's vast and rich bridge heritage.

However, the scale of the country is such that these represent only the tip of a very, very large iceberg. Luckily for us ignorant gwailo, Knapp and Ong's book helps expose a little more of China's vast and rich bridge heritage.It's a lovely coffee-table tome, amply illustrated with Ong's excellent photographs of bridges both famous and unknown. I don't think there's a page without a good photo on it. It also draws extensively on historic Chinese prints and paintings, and is clearly a labour of love.

The book is in three parts. The first is a general history of "ancient" Chinese bridge building, a journey through different bridge forms ranging across "step-on block bridges" (stepping stones), megalithic stone beam bridges, traditional chain bridges and more. One thing that is peculiar is that despite a wealth of detail, little is said on the bridge designers and builders themselves - there's no figure like Perronet or Telford here. Partly this is because the book's focus is before the "engineering" age of bridge building, but it may also relate to a lack of available information, or to the inability of individual bridge builders to build a reputation across such a huge country. This section introduces a number of bridges covered in more detail later in the book.

The second part addresses Chinese bridges as "living architecture", and discusses the relationship of traditional folk culture, feng shui, and religion to Chinese bridge building and use. Many historic Chinese bridges were or remain the sites of Buddhist, Taoist, or other temples, and many more are decorated with traditional emblems intended to bring good fortune or ward off disaster. Attention to auspicious dates and rituals played an important part in the building of many bridges, to the extent that bridges sometimes lay half-complete for considerable periods awaiting the "correct" date to proceed to the next stage.

The main part of the book is a gazetteer of over thirty particularly remarkable structures, "China's fine heritage bridges". Knapp's text for each bridge often ranges far and wide beyond the structure itself. When discussing the garden bridges of Beijing, for example, the reader will learn as much about the history of the Palace gardens as about the structures that ornament them. For others, like the canal bridges of Zhejiang, the text discusses in detail local trades and crafts.

Not all the bridges are spectacular - several are essentially minor structures of little fame or historical significance. However, they amply demonstrate the charm of vernacular bridge building, and that's reason enough to feature them.

Easily the highlight of the bridges included is a thirty-page section on Chinese covered wooden bridges, particularly of the "woven timber arch-beam" type. These are perhaps less well-known (Troyano's supposedly comprehensive Bridge Engineering: A Global Perspective ignores them, for example), but for me they are the main attraction of the entire book. While there are many examples of covered bridges throughout the book, this section concentrates on a particular sub-species, exemplified by rough-hewn behemoths like the Yangmeizhou Bridge (pictured, left, from the book).

While some in this group consist of straight beam bridges, with some similarities to the well-known covered bridges of Switzerland and the USA, most are massive timber "arches", supported by logs interlocked together in a polygonal form. The structure is generally hidden behind timber slat cladding, giving them a coarse, inelegant appearance. I find them quite beautiful.

Knapp's own website has a series of PDFs illustrating a variety of Chinese covered bridges, but it's no substitute for holding this exceptional book in your hands.

13 October 2012

Bridges news roundup

Okay, time for blogging remains short, so while I prep something more substantial, here are a few links that might be worth a look:

Kiss Bridge / Joaquin Alvado Bañon

Kiss Bridge / Joaquin Alvado Bañon

Interesting twin-cantilever footbridge (pictured) over a flood channel in Spain.

Bridge Designs – 5 Most Ambitious of Today

A mixture of proposals, some likely to be built, some not.

Ross beauty spot bridge gets the big opening

£123k suspension footbridge opened at Rogie Falls, Scotland.

Bridge design team emphasises its local roots

Sssh, don't tell anyone the architect has been imported from the UK.

New "butterfly" bridge over the River Clyde

New "butterfly" bridge over the River Clyde

"Dalmarnock Smart Bridge" (pictured), designed by Halcrow, receives planning permission.

Brownlie and Ernst create infrastructure dream team

Dynamic duo comprised of ex-Wilkinson Eyre and ex-Dissing + Weitling specialist bridge architects.

Famous architect, artist will weigh in on Tappan Zee overhaul

Richard Meier and Jeff Koons called up to advise on aesthetics of Tappan Zee bridge replacement. Perhaps Koons will push to incorporate some Made in Heaven iconography. At least they didn't ask Andres Serrano.

PT bamboo pure: millennium bridge

PT bamboo pure: millennium bridge

Thoroughly delightful covered bamboo footbridge in Bali (pictured).

Venice's Rialto bridge will be desecrated by advertising

The bridge arcade in particular could certainly do with a scrub up, but the outrage seems over done - this is hardly a new idea.

Symbolic inauguration of 5,000th suspension bridge

Celebration for the building of 5000 bridges in Nepal with Swiss assistance. Quite an amazing achievement.

Kiss Bridge / Joaquin Alvado Bañon

Kiss Bridge / Joaquin Alvado BañonInteresting twin-cantilever footbridge (pictured) over a flood channel in Spain.

Bridge Designs – 5 Most Ambitious of Today

A mixture of proposals, some likely to be built, some not.

Ross beauty spot bridge gets the big opening

£123k suspension footbridge opened at Rogie Falls, Scotland.

Bridge design team emphasises its local roots

Sssh, don't tell anyone the architect has been imported from the UK.

New "butterfly" bridge over the River Clyde

New "butterfly" bridge over the River Clyde"Dalmarnock Smart Bridge" (pictured), designed by Halcrow, receives planning permission.

Brownlie and Ernst create infrastructure dream team

Dynamic duo comprised of ex-Wilkinson Eyre and ex-Dissing + Weitling specialist bridge architects.

Famous architect, artist will weigh in on Tappan Zee overhaul

Richard Meier and Jeff Koons called up to advise on aesthetics of Tappan Zee bridge replacement. Perhaps Koons will push to incorporate some Made in Heaven iconography. At least they didn't ask Andres Serrano.

PT bamboo pure: millennium bridge

PT bamboo pure: millennium bridgeThoroughly delightful covered bamboo footbridge in Bali (pictured).

Venice's Rialto bridge will be desecrated by advertising

The bridge arcade in particular could certainly do with a scrub up, but the outrage seems over done - this is hardly a new idea.

Symbolic inauguration of 5,000th suspension bridge

Celebration for the building of 5000 bridges in Nepal with Swiss assistance. Quite an amazing achievement.

07 October 2012

Scottish Bridges: Final summary

At last, that's over. I started posting reports on the bridges visited during a 3-day Scottish tour at the beginning of July, and it has taken until now to finish covering them all. There were 35 bridges seen over those three days, and this map shows the ground covered (blue is the first day, red the second, and green the third):

I said at the outset that "Several of the bridges are among those in Britain which any serious Pontist should try and visit once in their life".

These are the ones I would recommend going out of your way to see, if you get a chance:

I plan at some point to complete a similar tour of the western half of the Scottish highlands. In the mean time, now that this mammoth task of reporting on bridges is complete, I can get back to some more "normal" blogging. Next up, as soon as I get time, will be a series of book reviews.

I said at the outset that "Several of the bridges are among those in Britain which any serious Pontist should try and visit once in their life".

These are the ones I would recommend going out of your way to see, if you get a chance:

I plan at some point to complete a similar tour of the western half of the Scottish highlands. In the mean time, now that this mammoth task of reporting on bridges is complete, I can get back to some more "normal" blogging. Next up, as soon as I get time, will be a series of book reviews.

03 October 2012

Scottish Bridges: 54. Footbridge at Invermark

The grand finale. The pièce de résistance. This, believe it or not, was planned as the culmination of our entire Scottish bridge tour. And, I think, rightly so.

You won't find any information about this bridge online, indeed, so far as I can tell, the images I'm posting here are the first on the internet. It's in the middle of nowhere, across the River Esk, at the far end of the road in Glen Esk, close to Invermark Castle. It leads from a field across the river towards the hills, and I imagine is mainly there for the use of anglers. A sign at one end reads "Dalhousie Estates - Private estate bridge not for public use - any persons using the bridge do so at their own risk".

I first encountered this bridge through Mike Schlaich and Ursula Baus's excellent book, Footbridges, where it is accorded a two-page spread, ranking it up there along with some of the finest contemporary pedestrian bridges. Ever since then, I knew I had to see it for myself.

By the standards of some of the bridges to be found elsewhere in the world, this is a high-quality, sturdy structure. By contemporary British standards, it is a thrillingly ramshackle agglomeration of scrap metal and wood, the sort of thing you might imagine the man who repairs the fences on an upland farm throwing together. Which is precisely what seems to have been the case here.

The bridge appears to be held aloft largely by the power of wishful thinking. At first glance, you may note the presence of suspension wires at either side, and assume that these support the deck, but in fact these are merely there to hold the wire-mesh "parapets" in place. The bridge deck is of the catenary suspension form, comprising three timber planks, with occasional cross-planks, supported on precisely seven strained fencing wires. These provide the primary, possibly the only, means of support.

The support wires are braced via cross-members against the tree-trunk masts, which in turn are held back by stay wires, anchored into further timbers driven into the ground. Mesh-link fencing at either side of the approaches to the bridges steers the traveller towards the steps, and presumably serves the more important function of keeping livestock from pulling the wires down.

Lateral tie wires have been installed to reduce lateral sway, although even with these in place, this is possibly the most precarious bridge that I have ever crossed. It's hard to escape the feeling that you will be pitched into the river at any moment.

At one end of the bridge, the main deck support wires are wound round tensioning ratchets. At the other end, they are simply turned round a cross-bar and twisted together. This really is all that holds you up while you cross.

Everything about this bridge is brilliant. It's an adventure to use, a heart-punching antidote to the sanitised world of health-and-safety that binds most bridge designers. It's also a splendid example of the charms of vernacular design. Can anyone imagine a professional designer producing something so intriguingly crafted?

It provided a fine end to our trip.

Further information:

You won't find any information about this bridge online, indeed, so far as I can tell, the images I'm posting here are the first on the internet. It's in the middle of nowhere, across the River Esk, at the far end of the road in Glen Esk, close to Invermark Castle. It leads from a field across the river towards the hills, and I imagine is mainly there for the use of anglers. A sign at one end reads "Dalhousie Estates - Private estate bridge not for public use - any persons using the bridge do so at their own risk".

I first encountered this bridge through Mike Schlaich and Ursula Baus's excellent book, Footbridges, where it is accorded a two-page spread, ranking it up there along with some of the finest contemporary pedestrian bridges. Ever since then, I knew I had to see it for myself.

By the standards of some of the bridges to be found elsewhere in the world, this is a high-quality, sturdy structure. By contemporary British standards, it is a thrillingly ramshackle agglomeration of scrap metal and wood, the sort of thing you might imagine the man who repairs the fences on an upland farm throwing together. Which is precisely what seems to have been the case here.

The bridge appears to be held aloft largely by the power of wishful thinking. At first glance, you may note the presence of suspension wires at either side, and assume that these support the deck, but in fact these are merely there to hold the wire-mesh "parapets" in place. The bridge deck is of the catenary suspension form, comprising three timber planks, with occasional cross-planks, supported on precisely seven strained fencing wires. These provide the primary, possibly the only, means of support.

The support wires are braced via cross-members against the tree-trunk masts, which in turn are held back by stay wires, anchored into further timbers driven into the ground. Mesh-link fencing at either side of the approaches to the bridges steers the traveller towards the steps, and presumably serves the more important function of keeping livestock from pulling the wires down.

Lateral tie wires have been installed to reduce lateral sway, although even with these in place, this is possibly the most precarious bridge that I have ever crossed. It's hard to escape the feeling that you will be pitched into the river at any moment.

At one end of the bridge, the main deck support wires are wound round tensioning ratchets. At the other end, they are simply turned round a cross-bar and twisted together. This really is all that holds you up while you cross.

Everything about this bridge is brilliant. It's an adventure to use, a heart-punching antidote to the sanitised world of health-and-safety that binds most bridge designers. It's also a splendid example of the charms of vernacular design. Can anyone imagine a professional designer producing something so intriguingly crafted?

It provided a fine end to our trip.

Further information:

- Google maps

- Footbridges (Baus / Schlaich, 2008)

01 October 2012

Scottish Bridges: 53. Loups Bridge

Loups Bridge is another of John Justice Jr's structures. We'd been to his other bridges at Crathie, Kirkton of Glenisla, and Haugh of Drimmie, and Loups Bridge completes the set: the only other Justice bridge known to survive.

Loups Bridge spans the River North Esk not far from Edzell. I guess it is named for the waterfall which cuts through a rocky channel just below it, "loups" referring to a salmon leap.

The bridge is on private land, and I'm not clear whether normal Scottish rights of access to walk across the land apply, as it is in the grounds of a partially residential building. The Happy Pontist had obtained permission from the landowner to visit the bridge on this occasion.

The bridge has two spans, supported by a masonry pier at its centre. The RCAHMS website lists the spans as 9m and 10m, but also states 15m and 17.4m, while Ruddock's paper lists two equal 36 foot spans. I don't know which is right.

The bridge is Listed Grade B, and seems of considerable historic importance as a rare example of the Justice family's work, and also as one of the earliest surviving stayed bridges in the UK. Its exact date of construction is unknown. It may possibly pre-date the stayed footbridge at Kirkton of Glenisla, which was built in 1824, or the Haugh of Drimmie bridge from 1823.

Unlike the other Justice bridges that we visited, Loups Bridge is derelict. Very little of it remains, and it would be foolhardy to try and walk across it. It is more than a ghost of a bridge, but only barely so.

From what can be seen, it's clear that the bridge's skeleton must have been exceptionally slender even by the standards of other Justice spans. The stay rods and cross-members are tiny in cross-section, and the odd arched pylons above the pier are not made out of anything more substantial. There are two wire-like stringers which must once have been below a timber deck, and I would guess there were once longitudinal edge members providing tension ties to the inclined stays. Most of what now remains would once have formed the wire-fence balustrades.

It would make for a very interesting restoration project, but I suspect this bridge is well past the point where it can be repaired.

Further information:

Loups Bridge spans the River North Esk not far from Edzell. I guess it is named for the waterfall which cuts through a rocky channel just below it, "loups" referring to a salmon leap.

The bridge is on private land, and I'm not clear whether normal Scottish rights of access to walk across the land apply, as it is in the grounds of a partially residential building. The Happy Pontist had obtained permission from the landowner to visit the bridge on this occasion.

The bridge has two spans, supported by a masonry pier at its centre. The RCAHMS website lists the spans as 9m and 10m, but also states 15m and 17.4m, while Ruddock's paper lists two equal 36 foot spans. I don't know which is right.

The bridge is Listed Grade B, and seems of considerable historic importance as a rare example of the Justice family's work, and also as one of the earliest surviving stayed bridges in the UK. Its exact date of construction is unknown. It may possibly pre-date the stayed footbridge at Kirkton of Glenisla, which was built in 1824, or the Haugh of Drimmie bridge from 1823.

Unlike the other Justice bridges that we visited, Loups Bridge is derelict. Very little of it remains, and it would be foolhardy to try and walk across it. It is more than a ghost of a bridge, but only barely so.

From what can be seen, it's clear that the bridge's skeleton must have been exceptionally slender even by the standards of other Justice spans. The stay rods and cross-members are tiny in cross-section, and the odd arched pylons above the pier are not made out of anything more substantial. There are two wire-like stringers which must once have been below a timber deck, and I would guess there were once longitudinal edge members providing tension ties to the inclined stays. Most of what now remains would once have formed the wire-fence balustrades.

It would make for a very interesting restoration project, but I suspect this bridge is well past the point where it can be repaired.

Further information:

- Google maps / Bing maps

- RCAHMS

- British Listed Buildings

- Aberdeenshire SMR

- Some iron suspension bridges in Scotland 1816-1834 and their origins (Ruddock, The Structural Engineer, 2003)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)